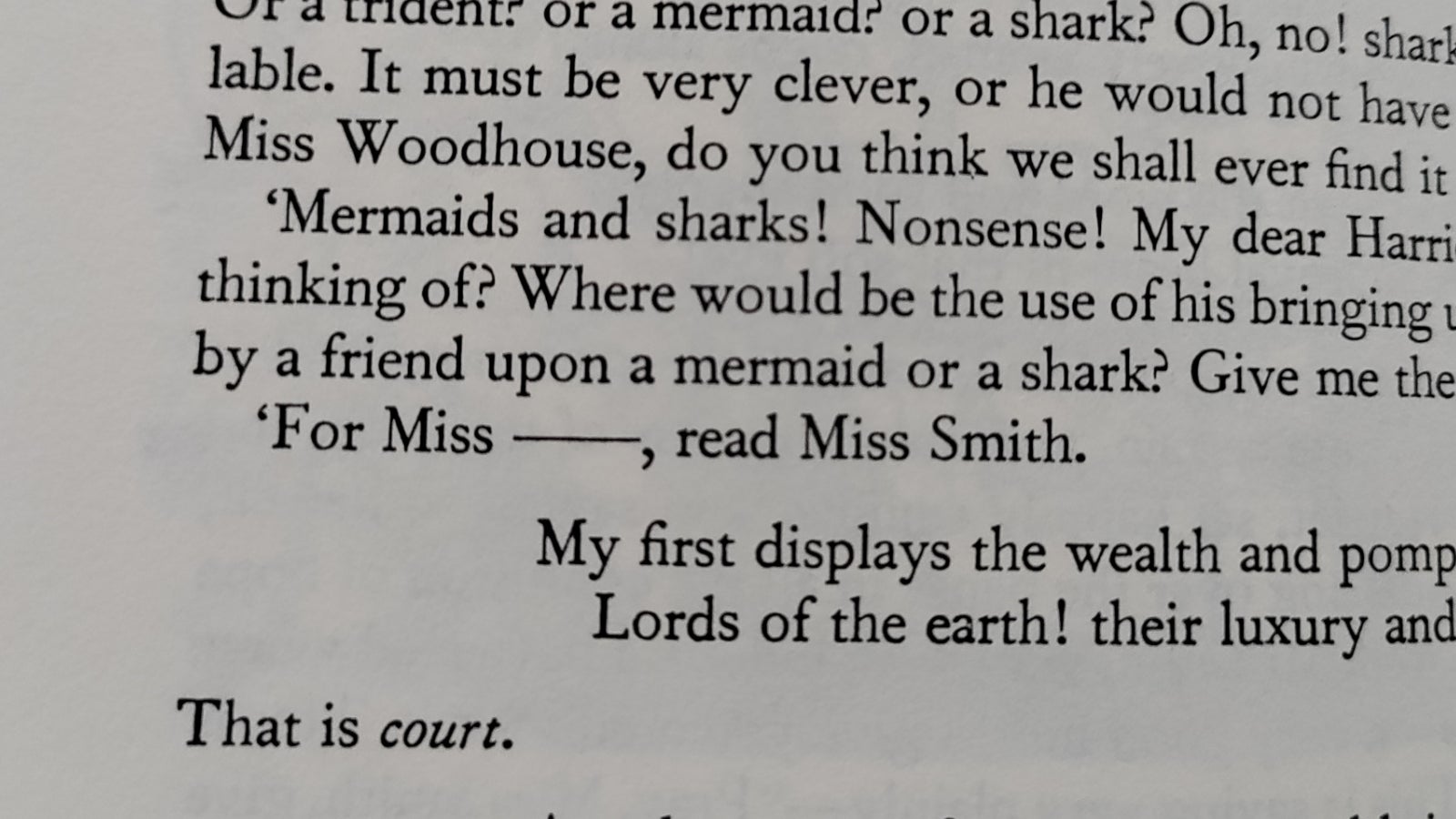

A picture from Jane Austen’s Emma referring to a “Miss —-“

A picture from Jane Austen’s Emma referring to a “Miss —-“It’s taken me more than a month, but I’ve finally gotten back into the swing of reading for fun.

And with 2005′s Pride and Prejudice reaching its 20th anniversary (and Emerald Fennell’s Netflix adaptation of Wuthering Heights well on its way), I’ve returned to an old favourite: folks, she’s back on the Austen.

But a recent scroll of Reddit’s r/janeausten showed some fellow readers are wondering about a hallmark of the author’s writing – her long, mysterious blanks where people or places’ names should be.

So, we spoke to Cambridge University’s Professor Janet Todd, author of the freshly-released Living With Jane Austen (which coincides with Austen’s 250th birthday) and 2006′s The Cambridge Introduction to Jane Austen, about what’s really going on here.

It makes the work seem real

Austen is far from the only writer who used the technique.

It appeared in, for instance, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (which mentions the rather Google Maps-unfriendly “town of ——”), and showed up in real-life papers of the 19th century too (The Times in 1837 wrote, “Some time after the party had returned to D―- House, Mrs. C―- discovered that she had lost a very fine boa…”).

Professor Todd says these dashes are “a device to pretend that the story is real.”

It makes the work “look authentic,” as though the author is worried about real people finding themselves unexpectedly represented in her print.

“Also,” Professor Todd continues, this way the author “avoids referring to a real place or person.”

It likely didn’t hurt that the technique saved Austen “the trouble of making names up” too.

Professor Todd isn’t alone

Writing for The Atlantic in 1967, John Barth shared that “Initials, blanks, or both were often substituted for proper names in nineteenth-century fiction to enhance the illusion of reality.”

He added, “It is as if the author felt it necessary to delete the names for reasons of tact or legal liability.”

In the case of stories based on, or inspired by, real-life people or places, that may be especially useful; either way, it certainly saved writers some time.

A picture from Jane Austen’s Emma referring to a “Miss —-“It’s taken me more than a month, but I’ve finally gotten back into the swing of reading for fun.And with 2005′s Pride and Prejudice reaching its 20th anniversary (and Emerald Fennell’s Netflix adaptation of Wuthering Heights well on its way), I’ve returned to an old favourite: folks, she’s back on the Austen. But a recent scroll of Reddit’s r/janeausten showed some fellow readers are wondering about a hallmark of the author’s writing – her long, mysterious blanks where people or places’ names should be. So, we spoke to Cambridge University’s Professor Janet Todd, author of the freshly-released Living With Jane Austen (which coincides with Austen’s 250th birthday) and 2006′s The Cambridge Introduction to Jane Austen, about what’s really going on here. It makes the work seem realAusten is far from the only writer who used the technique.It appeared in, for instance, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (which mentions the rather Google Maps-unfriendly “town of ——”), and showed up in real-life papers of the 19th century too (The Times in 1837 wrote, “Some time after the party had returned to D―- House, Mrs. C―- discovered that she had lost a very fine boa…”). Professor Todd says these dashes are “a device to pretend that the story is real.”It makes the work “look authentic,” as though the author is worried about real people finding themselves unexpectedly represented in her print. “Also,” Professor Todd continues, this way the author “avoids referring to a real place or person.”It likely didn’t hurt that the technique saved Austen “the trouble of making names up” too. Professor Todd isn’t aloneWriting for The Atlantic in 1967, John Barth shared that “Initials, blanks, or both were often substituted for proper names in nineteenth-century fiction to enhance the illusion of reality.”He added, “It is as if the author felt it necessary to delete the names for reasons of tact or legal liability.”In the case of stories based on, or inspired by, real-life people or places, that may be especially useful; either way, it certainly saved writers some time.Related…Who Cares About Pride And Prejudice’s New Darcy? Austen Knew He Was Never The Real Romantic LeadNetflix’s New Version Of Jane Austen’s Persuasion Branded ‘Horrible’ And ‘A Travesty’ By CriticsHere’s Why Pride And Prejudice’s 2005 UK Ending Was So Different To The US’ Life, trivia, books, jane austen, jane-austen HuffPost UK – Athena2 – All Entries (Public)