Bitcoin Magazine

Maya Parbhoe’s Credibility Crisis: Suriname Unlikely To Be Next Bitcoin Country

Last year, Maya Parbhoe quickly became well-known in the international Bitcoin community as she presented herself to the world as a presidential candidate in her country, Suriname. She vowed to fight corruption in a country rife with it and to make bitcoin legal tender in Suriname to help get the country’s citizens out of financial “survival mode.”

Parbhoe’s story as an underdog candidate quickly gained traction as she made her case for how she could help Suriname as president both online and in person at conferences such as Bitcoin Amsterdam.

Prominent members of the Bitcoin community such as Bitcoin mining analyst and leadership coach Daniel Batten have vouched for Parbhoe in recent months, while Jan3 CEO Samson Mow was the one who encouraged Parbhoe to run for president. I, too, helped bring attention to her candidacy.

However, in recent weeks, some cracks have started to form in Parbhoe’s story. Reports from those who have visited the country say that the image that Parbhoe has been projecting of herself and her candidacy to the world may be in part an illusion.

The reports claim that Parbhoe has overstated her odds of becoming president of Suriname to the international community and that her political messaging within the country has had little to nothing to do with Bitcoin.

What is more, some reports that are now reaching the international Bitcoin audience also contend that Parbhoe’s candidacy is not well known within Suriname. And while Parbhoe has positioned herself as an advocate for those within her country who are struggling financially, one source told Bitcoin Magazine that she has disdain for the country’s poor.

On top of that, reported intel from the U.S. government estimates that Parbhoe may be running as “controlled opposition,” a political figure who serves as a placeholder for those that they purport to be against. According to Bitcoin Magazine’s source, the same reported intel states Parbhoe’s father was knowingly in business with drug traffickers and money launderers and that there’s also a chance that the bank accounts for Parbhoe’s companies are being used to launder money.

Before diving deeper into the latter allegations, it’s first important to understand the depths of corruption in Suriname and how Parbhoe claims to be an antidote to it.

Parbhoe’s Anti-Corruption Political Campaign

According to a 2022 report from the U.S. Department of State, almost every sector of Suriname’s government has been accused of corruption. These sectors include the central bank of Suriname and state-owned companies, including the country’s national airline, Surinam Airways, and the government health insurance company, SZF.

Some of the highest-ranking individuals in the country have also been involved in corruption, as the country’s current vice president has been convicted of drug trafficking and the country’s former president, Dési Bouterse, was convicted of drug trafficking and murder and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Parbhoe billed herself as an anti-corruption presidential candidate in Suriname’s upcoming elections, which are slated to occur on May 25, 2025.

As part of her messaging, she often mentions how her father was murdered for speaking out against corruption in the country, and she says that she wants to carry on his legacy by speaking out against corruption in Suriname, as well.

The part of this story that Parbhoe has left out as she’s recounted it time and time again, though, is that her father had two Colombian partners in his casino business who he knew were also involved in drug trafficking and money laundering. According to a former senior advisor for Parbhoe’s campaign, Shamay, Parbhoe is aware that her father knew he was in business with these people, as she has told him as much.

Micah Dunford, a retired Green Beret and CEO of Greyscale Protection, a company that Parbhoe contracted to protect her during the beginning of April, when she gave birth to her daughter, informed Bitcoin Magazine that reported intel from the U.S. government states that Parbhoe’s father was knowingly involved with “nefarious actors” and was murdered by “narco terrorists.”

[Author’s note: Dunford would like to make it clear that he only shared the information above as well as other information in this piece about a client of his because he is a Bitcoin enthusiast and feels that Parbhoe is doing a great disservice to the Bitcoin community and to Bitcoin’s reputation.]

When I initially interviewed Parbhoe in July 2024, she offered an account of her father’s business dealings that did not include his knowingly being in business with drug traffickers and money launderers. She stuck to her original story and denied that her father was in business with two Colombian drug traffickers when I recently reached out to her to ask her about the matter.

“My father was in business with Dorsett Resorts,” Parbhoe told Bitcoin Magazine via email.

“It was a publicly traded company in the U.S. and he bought $500,000 in shares so he could be in investor meetings. My father went to the then Minister of Justice, Santhokhi, and all authorities, including the three letter agencies, when he realized what was going on,” she added.

“His case against de [De] Surinaamsche Bank is currently being delayed by the president at our highest court of justice. The case against the CEO, COO and Manager from Dorsett goes to court on April 28th. I am his only living heir fighting this case.”

If Parbhoe’s father was knowingly in business with drug traffickers and if Parbhoe knew that he knew this and continues to omit it from the story of her father’s murder that she tells the media, what she’s doing is part of a broader trend when it comes to some of the stories she tells — including the one about her becoming president of Suriname.

Suriname’s Electoral System

In Suriname’s political system, a parliamentary democracy, voters elect candidates to represent them in parliament, the 51-member National Assembly.

Historically, most voters vote for the leader of a political party, and if that leader won enough votes for more than one seat, the additional seats went to members of their same party in predetermined order based on their position on the party’s candidate list — the higher on the list, the better the odds of winning a parliamentary seat.

Although it was technically possible for a candidate lower on the list to be elected into parliament directly if enough people vote on this candidate specifically (rather than the party leader), this rarely happened.

Once parliamentarians were elected, coalitions would form in parliament, and its members would then vote on a president. The National Assembly would then elect the president by a two-thirds vote — 34 of 51.

This dynamic will partially shift in upcoming elections, though, as Suriname is implementing a new “one person, one vote” system.

Suriname’s New Electoral System: One Person, One Vote

In August 2020, the Constitutional Court of Suriname ruled the former electoral law in Suriname unconstitutional in that it violated the principle of one person, one vote, according to the aforementioned 2022 report from the U.S. Department of State.

The document states that “the court found that votes in rural, less populated districts outweighed those in urban, more populated areas, since it required far fewer votes to win a seat for the National Assembly in rural districts [and it] mandated that the government and National Assembly amend the legislation as soon as possible for the 2025 elections to take place on time.”

Under the new system, each voter votes for one member of parliament, and each party has 51 candidates for the 51 seats of parliament.

Seats are divided between the different political parties based on the total number of votes on all candidates for these parties. These seats then go to the candidates of each of these parties that got the most votes individually. So, if a political party gets (say) five seats in parliament, those five seats will go to the five candidates of that party with the most individual votes; their ranking on the party’s candidate list is irrelevant.

Any group of at least seven members of parliament (regardless of party affiliation) can submit a candidate for president. Parliament then votes based on that list of candidates, and a two-thirds majority vote determines who wins the presidency.

Parbhoe’s Strategy To Become President

Parbhoe, who is not the head of the political party with which she’s affiliated, the National Party of Suriname (NPS), is looking to capitalize on this new system by aiming to get as many votes as possible in the general election.

She said that she would need 5,380 votes to win a seat in parliament, which she believes she can get. (This seems logical in that 283,834 people voted in Suriname’s 2020 election, and if each of the 51 candidates elected to parliament received 5,380 votes, this would mean that 274,380 people voted, which is very close to the voter turnout from the previous election. Also, under the old electoral system, Parbhoe would have needed a minimum of 7,000 votes as a candidate based in Paramaribo, the largest constituency in the country.)

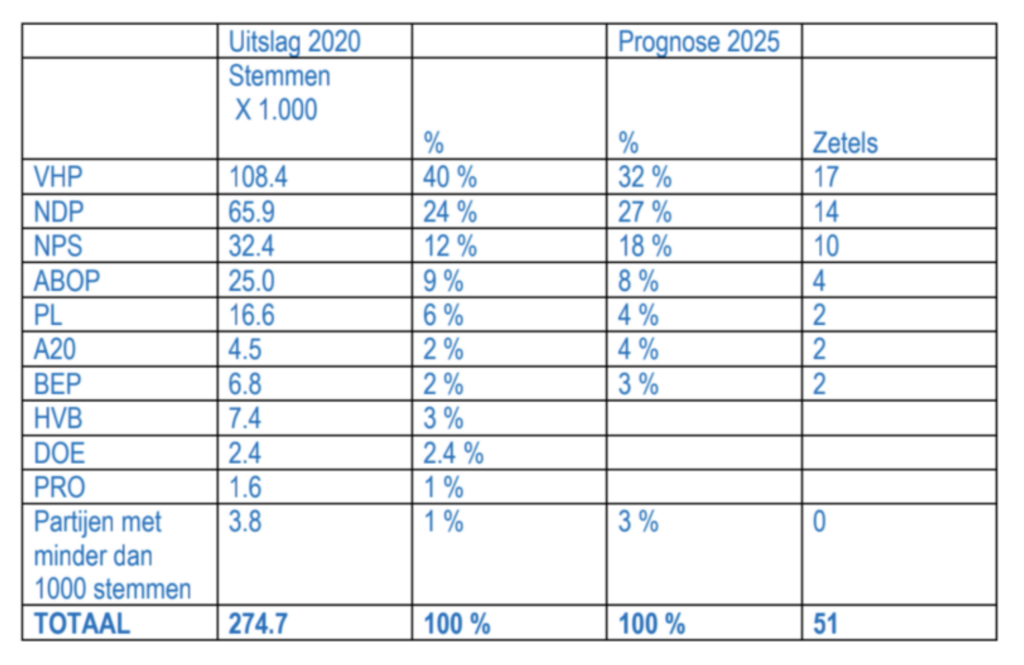

A poll conducted on April 21, 2025 shows that NPS may win 10 seats in parliament (7 more than they currently have), but the poll doesn’t indicate which of NPS’s candidates are most popular.

However, this doesn’t matter much to Parbhoe anyway because winning a seat in parliament is what she calls a “worst case scenario.”

This is because her goal isn’t to become a member of parliament — it’s to become president.

“I am not running for a seat in the National Assembly,” she wrote in an email to me.

Parbhoe is aiming for a best-case scenario in which she gets the most votes in the country, as “usually, the candidate with the most votes gets elected by members of parliament to become president,” according to her. (What she didn’t mention, though, is that the candidate who almost always gets the most votes is the leader of the biggest political party.)

She acknowledged that the leader of NPS, Gregory Rusland, is one of her biggest competitors. A report shows that in a recent poll on the most popular presidential candidates in Suriname, Rusland ranked fourth. (Parbhoe wasn’t mentioned in the report.)

Parbhoe believes that part of her edge is that she’s a younger candidate (She is 37 years old). She noted that Rusland is over 60 years of age, while the majority of the voters in the country are under the age of 45.

Parbhoe also added that “most of the candidates that have announced that they are running for president have an equal shot [of winning] as I do,” without commenting on what those odds are.

The Decreased Significance of Rank Within Political Parties in Suriname

In a Reddit post on April 13, Michel Greijmans, a businessman based in Curaçao who visited Suriname for work in February, commented that Parbhoe has less of a chance of winning the presidency because she is ranked number 21 within the NPS.

What Greijmans didn’t acknowledge, though — probably because he was not privy to this information — is that Parbhoe, by her own account, strategically selected this ranking of number 21 as an ode to Bitcoin, because rank within a party is mostly irrelevant now anyway.

Parbhoe first informed me of her doing this via text weeks back when her rank within the party was first announced, and she reiterated this to me in our most recent communications.

Had she not selected number 21, she said she would have opted for a ranking at the bottom of the list of her party (number 50 or 51). In Surinamese parliamentary system — at least in the older version of it — when a candidate selects the lowest ranking within a party, it’s a signal that they aren’t necessarily running for a seat in parliament, but are on the list just to endorse a particular party. (This type of candidate is sometimes referred to as a Lijstduwer, which translates to “list pusher,” and it exists in the Surinamese and Dutch parliamentary systems. List pushers often include celebrities, artists, or athletes who have no intention of serving in parliament.)

This type of candidate is sometimes referred to as a Lijstduwer, which translates to “list pusher,” and it exists in the Surinamese and Dutch parliamentary systems. List pushers often include celebrities, artists, or athletes who have no intention of serving in parliament. (Such a candidate in Suriname’s current electoral race is Ingrid Bouterse-Waldring, widow of the late Dési Bouterse, the aforementioned former president of Suriname. She’s ranked number 51 within the NPS.)

So, aside from Parbhoe’s being a new, young candidate, what else is she doing to differentiate herself from the competition?

Well, she’s broadcasted to the international Bitcoin community that she plans to replace Suriname’s national currency, which has an average yearly inflation rate of 8.7% and which spiked as high as 59% in 2020, with bitcoin.

However, those who’ve visited Parbhoe in Suriname and who have reported back to the international Bitcoin community have said that Bitcoin is hardly part of her messaging within the country and that her strategy to replace the national currency with bitcoin won’t work.

The Reality On The Ground: Parbhoe’s Lack Of A Bitcoin Strategy

Greijmans, in his aforementioned Reddit post, mentioned that, in his experience on the ground in Suriname, no one outside of Bitcoin circles knew who Parbhoe was and that those within Bitcoin circles in the country didn’t want to talk about her.

Dr. Jack Kruse, who’d met with Parbhoe on the ground in Suriname in February and even gave a nationally-televised talk on reforming Suriname at an NPS event during this visit, claimed on X that Greijmans’ experience was comparable to his own.

I followed up with Greijmans to learn more about his experience on the ground.

Greijmans’ Take

“The fact that the people I spoke to didn’t want to talk about her raised concerns for me,” Greijmans told Bitcoin Magazine.

Greijmans didn’t speak up about his experience immediately after his visit, though, because he felt it was possible that members of the local Bitcoin community were simply trying to distance the community that they were building from her campaign.

He also noted that members of the Bitcoin community on the ground in Suriname are doing “tremendous work” and that he doesn’t want the damage that Parbhoe might be doing to blow back on the community there. (Kemal Yaşar, Marketing Director for Blink Wallet, confirmed that the number of transactions by Blink users in Suriname increased 2,389% from July 2024 to March 2025.)

To Parbhoe’s credit, she established the Bitcoin community that Greijmans visited, Bitcoin Sranan, in 2021.

Greijmans also noted that as of the second week of April, Parbhoe had revamped her website, removing all claims that she is running for president.

His main issue with Parbhoe was that she was projecting an image to the world about her candidacy that’s far from the reality on the ground.

He said that one of his motivations in writing the Reddit piece was to let the international community know that Parbhoe seemed to be taking advantage of the fact that it was easy for her to project a certain image to an international audience, as her actions are difficult to audit for those who aren’t on the ground in Suriname.

“I wanted to at least alert people like, ‘Hey, listen, you’re dealing with a culture, a political system, a country that’s very opaque to its international audience,’” said Greijmans.

Parbhoe’s Chief Economic Advisor’s Take

Rahim Taghizadegan, Parbhoe’s chief economic advisor, claimed in a recent X post that, when he visited Suriname, he also found that the reality on the ground was different from the image Parbhoe had been projecting to the world.

“It did not surprise me in the slightest that the on-the-ground reality — regarding both Bitcoin adoption and Maya’s actual role — fell significantly short of the media hype,” wrote Taghizadegan.

Taghizadegan also mentioned that he’d communicated to Parbhoe that her plan to make bitcoin the primary currency in Suriname wasn’t realistic, an assessment she wasn’t fond of.

“Maya disliked my assessment that her proposal to convert the national currency directly into [b]itcoin by governmental decree was unfeasible,” he wrote.

Furthermore, Taghizadegan also noted Parbhoe’s shortcomings as a businesswoman.

“Her business track record revealed deficiencies in judgment and execution, but this was hardly unexpected and quite typical for someone transitioning into politics,” he added.

Parbhoe’s Former Senior Campaign Advisor’s Take

Shamay, who first met Parbhoe at Adopting Bitcoin El Salvador in November 2024 and began communicating with her soon after, visited Parbhoe in Suriname twice, once in January and once in February of this year, also voiced concerns about Parbhoe based on her lack of ability to execute as well as her poor business acumen.

While he was with Parbhoe on the ground, Parbhoe tearfully told him that the companies she’d founded — Quickship Logistics, Icarus Geosystems, and Daedalus Labs — weren’t profitable, but that she had to keep up the image that they were successful or she wouldn’t be respected as a young woman in politics in Suriname. He added that she was very fearful that this fact might get out and ruin her reputation.

Another source familiar with the matter confirmed that Quickship Logistics is not profitable, and that Parbhoe uses funds from the company to pay for personal expenses.

Shamay was also taken back at how disorganized Parbhoe’s political campaign was.

He said that the campaign was being run from her living room couch with a few unpaid team members and that there was “no discussion about bitcoin.”

“Parbhoe did not have a Bitcoin platform within Suriname,” said Shamay.

Because of what he saw in his visits with Parbhoe, he withheld a mid-six-figure donation that he planned to give to her campaign.

A Greyscale Security Team Members’ Take

One of the members from Greyscale’s security team who went to Suriname wasn’t as concerned about Parbhoe’s lack of focus on bitcoin, which he still noted, as he was with how Parbhoe treated the less fortunate in the country.

“She speaks to people based on how they dress and how they present themselves,” the security team member told Bitcoin Magazine.

“If they are poor, you can tell that she does not give a flying shit about them. We would walk through the streets, and if somebody walked past her or walked too close to her, she would act like they were dirty — she did not like these types of people being around her,” he added.

(Taghizadegan also commented on Parbhoe’s behavior toward others in his X post. He wrote that “She was unkind to many people.”)

Parbhoe also demeaned and belittled both this security team member and his partner on the ground, he said.

According to the security team member, she asked him how much money he made, and when he told her, she responded by saying, “I didn’t know you’re one of the poors.”

The security team member also noted that Parbhoe’s critique of him seemed ironic since Parbhoe herself didn’t seem to have much money (though, he reported that she owns a Mercedes-Benz), and almost every source for this piece said that Parbhoe either owes them money, owes someone that they know money, or owes someone with whom she works money.

According to the security team member, she repeatedly asked to either borrow money from him or for him to pay for things like her groceries or dinner at a restaurant because she couldn’t afford them.

Ironically, Parbhoe claims that having to pay Greyscale, which provided its services to her at a discount, is part of the reason she doesn’t have the funds she needs to run her campaign properly or to help those she claims to help.

“[My] chances [of winning] decrease if I pay companies like Greyscale 3x for [a] contract and they deplete us out of funds,” wrote Parbhoe, alluding to the notion that Greyscale had overcharged her.

“I have projects for the teachers (painting schools, materials for the kids), orphanages (we still deliver food daily and have also planned sports/play days for them) and nurses (they’ve planned delivery of 70 bags with products new moms need) with deadlines and now less resources to complete,” she added.

“If I need to pick between airtime, billboards, and actual projects that help people, I will always pick the latter.”

(Shamay told me that she recently purchased a billboard for her campaign for $35,000.)

Parbhoe also suffers from insomnia, according to the security team member, and every hour and a half during the night, Parbhoe would come out of her room and turn the lights on in the room in which the security team members were sleeping on couches.

“She would flip the lights on and say ‘If I’m awake, you’re awake,’” said the security team member.

What is more, early one morning, she made the security team member with whom I spoke move to the floor to sleep.

“She came out to the couch and said, ‘You’re in my spot — get out. You can sleep on the floor,’” said the security team member. “For the rest of the time that we stayed at that house, I just slept on the floor in the kitchen, and it was horrible.”

Furthermore, this security team also said that Parbhoe became paranoid that her stepfather was trying to kill her because he’d left a cereal box on a panini press in her hospital room. She thought he was trying to start a fire next to her bed.

This sort of paranoia and irrational thinking had started weeks earlier, and the broader world started to get a glimpse of it on April 2, 2025.

The SOS and ‘Help’ Messages On X

On April 2, Parbhoe posted both a “Help” message on X and also recorded a 6-minute Space entitled “Life and family under threat. SOS,” which didn’t feature any evidence of a threat. Both the tweet and the Space were only recently deleted.

Many in the Bitcoin community who are on X became concerned, as there were no reports of her status for the hours that followed.

Hours after the original messages, she posted another message on X in which she stated “The US Secret Service is here in Suriname to protect me and to help me uncover corruption.” (This message has since been deleted.)

Days later, Parbhoe stated in an X post that it was because she was “under heavy medication and recovering from childbirth” that she inaccurately posted about the Secret Service protecting her. The latter portion of that statement is untrue, though, because Parbhoe hadn’t given birth by the time she’d published the X post.

Furthermore, two sources confirmed that Parbhoe was under no immediate threat when she made the initial two posts.

Hiring Greyscale

In the days leading up to Parbhoe’s entering the hospital in preparation to give birth, she grew increasingly paranoid that “they” were going to kill or harm her while she was giving birth.

“They” included the hospital staff and her political opposition. Dunford surmised that Parbhoe’s emotional state in this situation was a result of a combination of her being both paranoid and irrational in part because she was being “controlled by the opposition.”

“She is under their thumb,” said Dunford. “They most likely wanted to cut ties because she wasn’t endorsed to run a campaign and/or went off the reservation either politically or businesswise with whomever she is in bed with — which is most probably a combo of government [officials] and narcos, which are synonymous in Suriname.” (More on this in the following section.)

Around this time, Parbhoe sent repeated erratic messages to the cofounder of Bitcasa Homes, Amanda Dawn.

Dawn had been introduced to Parbhoe a year and a half prior, and the two had worked together in a small capacity as their respective companies (Daedalus Labs for Parbhoe) were focused on the intersection of bitcoin and real estate.

On March 26, 2025, Parboe had reached out to Dawn, frantically claiming that her life was being threatened.

Dawn was rattled by the desperation in Parbhoe’s voice. (I can relate to how Dawn likely felt, as I’ve received my fair share of panicked messages from Parbhoe, especially as her child’s due date approached. She has a strong ability to arouse sympathy and/or empathy from those with whom she engages.)

Dawn, who believed deeply in Parbhoe’s alleged pro-Bitcoin mission in Suriname, reached out to a contact at Bitcoin Veterans, stating that she needed to quickly find protection for Parbhoe.

That contact connected her with Dunford at Greyscale.

Dunford was familiar with Parbhoe’s purported mission to bring Bitcoin to the people of Suriname and agreed to offer his company’s services to Parbhoe while waiving his personal fee.

In the following days, Dunford sent two of his team members to guard Parbhoe, one a combat medic who is capable of delivering babies, as she gave birth.

Parbhoe didn’t sign the contract with Greyscale, as she claimed she was being forced to do so under duress, but Dunford sent help regardless. (Parbhoe never did sign the contract, which included a nondisclosure agreement. This is another reason Dunford is comfortable sharing information about the ordeal.)

Peter Kroll, founder of BTC Curaçao, sent bitcoin to Parbhoe for the purpose of paying the Greyscale bill.

Kroll also donated 0.5 bitcoin to Parbhoe during the latter part of 2024 and urged others to follow his lead by donating, though, he now regrets doing so.

He said that he very much believed in Parbhoe — someone he’d met through the virtual Bitcoin community Eenentwintig. He added that she had credibility because she’d “put time into the Bitcoin community.”

Parbhoe gave birth the day the Greyscale guards arrived.

And while Dunford’s men were with Parbhoe in the hospital and back at her home, a contact in the U.S. government shared intel on Parbhoe with Dunford.

That intel included information about Parbhoe being “controlled opposition” and potentially being involved with money laundering.

Controlled Opposition

Dunford shared that he was taken aback when he received this information on Parbhoe, as it shattered his illusion of her.

He wanted to believe she was the next Nayib Bukele — another pro-Bitcoin president — but what he learned from the intel changed his views on Parbhoe.

“She’s linked in with nefarious people,” Dunford told Bitcoin Magazine. “She’s controlled opposition — it’s not a real candidacy.”

As mentioned, controlled opposition refers to a situation where voters feel they have an option in an election, but the option is either owned financially or coerced into complying with the sitting power in some manner.

In Parbhoe’s case, Dunford believes that both are at play.

“The powers that be in the country have coerced her through financial manipulation and they own her,” said Dunford.

“This way, they could ensure that even if she got into some sort of power, that they would never be extradited to the EU,” he added. (When I first spoke with Parbhoe in July 2024, she said that the leaders of her country fear extradition, because, if extradited, they would be tried for the international crimes they’ve allegedly committed.)

“She puts on a policy platform that would make the people think, ‘Yeah, we’re going to fight the powers — we’re going to implement Bitcoin, blah, blah, blah, and that just isn’t true because they are pulling her puppet strings.”

Dunford also shared that he is a specialist in controlled opposition and information operations (i.e., propaganda campaigns). He added that he trains special operations forces (e.g., Green Berets) on these topics.

On the evening before the two Greyscale security team members left Suriname, “unknown entities, perhaps members of national security services,” attempted a forced entry into the hotel room in which the two Greyscale team members were staying to “change a lightbulb,” as the unknown persons put it, according to Dunford.

“Speaking as a guy that does this, if you have bad placement on a microphone or a camera, you’re not going to know that until you get back and you start to assess the audio and video — you might realize you can’t hear the conversation or that there’s something blocking the camera,” explained Dunford.

“So, they sent five really burly dudes to get into the hotel room to fix the batteries and the light or whatever it was, but we assessed that they were making a battery, camera, or microphone adjustment to correct their initial placement.”

I was in touch with these two Greyscale team members via text as this situation in the hotel played out, and they seemed genuinely concerned about their safety.

With that said, I was not able to find further information to corroborate that Parbhoe is “controlled opposition,” as Dunford put it.

Is Parbhoe Involved With Money Laundering?

According to Dunford, intel derived from an artificial intelligence system built by the U.S. government states that there’s a highly credible chance that the bank accounts for Quickship Logistics and Icarus Geosystems are being used to launder funds.

A source privy to bank records at Quickship Logistics said he didn’t get the sense that this sort of activity was happening through the company’s bank accounts, though.

If one of Parbhoe’s accounts were being used for such activity, it would more likely be the account for Icarus Geosystems, a company that builds infrastructure such as roads in remote regions of the country.

Parbhoe is the financial director of this company, and six-figure sums of money frequently flow through a bank account for the company, as per bank records obtained by Bitcoin Magazine.

I asked Parbhoe via email what some of the six-figure deposits were for via email and she responded with the following:

“Though Icarus is a private company, I can share that that’s revenue from projects currently in progress at Newmont and housing development and a retaining wall/channel project in Guyana.”

(Newmont is short for Newmont Corporation. The company has a subsidiary called Newmont Suriname, LLC — formerly Suriname Gold Company, LLC — which is a partially state-owned company.)

A company with the word “Newmont” in its name did in fact make a six-figure deposit on February 14, 2025.

In my research, I couldn’t find anything to confirm or corroborate the notion that funds are being laundered through Parbhoe’s companies’ bank accounts, nor that she is involved with money laundering in any other way.

Delusional, But Not A Criminal Mastermind

A number of sources described Parbhoe as “delusional,” “narcissistic,” and “mentally unstable,” but almost all of them were reluctant to call her a criminal.

“She’s more delusional than fraudulent,” is how one source put it. “She’s also very good at spinning the truth.”

In my personal interactions with Parbhoe, I’ve witnessed her stretch the truth on a number of occasions.

An example of this is last year at Bitcoin Amsterdam where I overheard her tell someone that she is an Oxford Alumni, when, in reality, she’s only completed a weeks-long certificate program at the university — not a proper degree.

Where Did the Bitcoin Donations Go?

According to Mick, the founder of Geyser Fund, Parbhoe’s Geyser campaign raised approximately $70,000 worth of bitcoin, as per bitcoin at a price of approximately $90,000.

(Other donors also donated to her campaign outside of Geyser, but those amounts haven’t been made public.)

Because of recent reports of Parbhoe’s lack of forthrightness, Geyser Fund has taken down Parbhoe’s “Maya for President” donations page.

For some time, Parbhoe published a campaign funds tracker, and she seemed to take pride in being transparent about where the funds were going.

She’s recently taken down the campaign funds tracker, though.

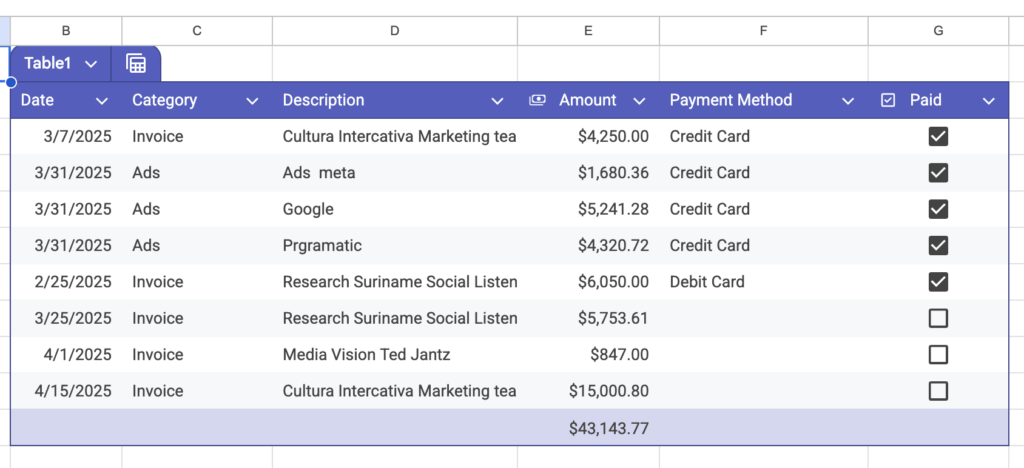

When I asked Parbhoe for an overview of expenses, she provided me with a link to this document (screenshot below), which only has eight line items.

Taghizadegan mentioned in his X post that some funds were spent on bringing renowned economist Arthur Laffer to Suriname to publicly voice his support for Parbhoe on the ground and on camera.

Parbhoe provided more information on this in my email communication with her.

“Arthur Laffer was engaged by a third party and paid by him, John, who himself negotiated terms with Dr. Laffer,” wrote Parbhoe. “He is engaged to be economic advisor once [I’m] elected.”

(Parbhoe didn’t make it clear who “John” was, but judging by the context in the email, it seems he was a major donor to the campaign.)

While in Suriname, Parbhoe conducted an on-camera interview with Laffer, which was published via the Bitcoin Magazine YouTube channel.

(When Parbhoe reached out to me about publishing the video, which I helped facilitate, she did not mention that Laffer was paid to visit Suriname.)

In the interview with Parbhoe, Laffer spoke about Parbhoe’s plans for Bitcoin adoption on the ground in Suriname.

However, there are no reports of him speaking about Bitcoin adoption with those with whom he engaged while on the ground in Suriname, despite the fact that he spoke with NPS about money and government financing.

“He gave a presentation for the NPS, which had a great impact on how the party views taxes and monetary incentives,” wrote Parbhoe.

Parbhoe also paid Daniel Batten $2,500 in total, though half of that funding came from Daedalus Labs, according to her.

Parbhoe wrote that Batten’s services were helpful in part because the breathing techniques he taught her helped her to cope with a situation that occurred approximately one week before she gave birth in which she was hospitalized and claims she was taken off of IV and left without water while she needed to be hydrated. She communicated this story to me shortly after this happened and believed it was an attempt on her life.

Shamay, who claims to have worked for her pro bono, said that she’d agreed to pay her campaign manager $15,000 per month, but her most recent campaign manager quit after only being paid $8,500 after two months.

Parbhoe’s aforementioned billboard expense cost the campaign $35,000, and she paid Greyscale $27,000 for its services.

Parbhoe Continues On

Parbhoe continues to campaign despite the challenges she’s faced as of late. However, she also says that the birth of her child has put the election in perspective for her.

“These last few weeks, I have undergone more trauma than I have endured my entire life,” wrote Parbhoe.

“The thought of losing my daughter, if you had given me 21 million Bitcoin, I would have spent it all to save her life. No election is worth her life,” she added.

“At this point, I don’t care if I win.”

Parbhoe also stated that whether or not she wins the election, she’ll continue to fight for Bitcoin adoption in Suriname past election day.

“I’ll do my best, I’ll fight for [my daughter’s] future and continue beyond May 25th,” wrote Parbhoe.

She concluded her final email to me with a quote from Bitcoin’s creator, Satoshi Nakamoto:

“If you don’t believe me or don’t get it, I don’t have time to try to convince you, sorry.”

What Parbhoe seemed to miss in making this final statement is that campaigning for political office is literally the process of convincing people that you’re the right person for the job. And, right now, many, including a number of former members of her team, don’t seem to feel that she is.

I don’t know for sure whether Parbhoe is controlled opposition or if she’s just someone struggling to execute a vision.

But I do know that trust is a difficult thing to win back — especially when it comes to the Bitcoin community — and her lack of forthrightness has done considerable damage to her reputation.

Having been in touch with Parbhoe on a semi-regular basis for the past eight months, I’d imagine, in her mind, her plan looked something like this:

- Announce underdog candidacy and leverage connections in the Bitcoin space.

- Bitcoiners from around the world come to my aid with donations and other types of campaign assistance.

- Forge a narrow path to victory to highest political position in Suriname, despite very low odds of such an outcome.

Some of this played out. The problem was that many who supported her eventually rescinded their efforts when they saw up close what was happening with Parbhoe.

But the most maddening part of this whole scenario is that if Dunford is right in that Parbhoe is “controlled opposition” — that her campaign has been little more than a ruse and that she’s working with “nefarious actors” behind the scenes — then the majority of this piece was written for naught and Parbhoe should simply be classified as the first major scammer of this cycle.

If this is the case, please accept my apology for helping to platform Parbhoe via Bitcoin Magazine.

And whether this is the case or not, this situation has been a strong reminder of the popular Bitcoin-related adage: Don’t trust, verify.

Some of us — myself included — should not so readily believe that certain characters in this space, especially political figures, are everything they purport to be.

This post Maya Parbhoe’s Credibility Crisis: Suriname Unlikely To Be Next Bitcoin Country first appeared on Bitcoin Magazine and is written by Frank Corva.

Bitcoin Magazine

Maya Parbhoe’s Credibility Crisis: Suriname Unlikely To Be Next Bitcoin Country

The Surinamese political candidate has projected an image of herself as a successful businesswoman running as a pro-Bitcoin presidential candidate to the international Bitcoin community, but those who’ve interacted with her on the ground — or those who’ve obtained reported government intel on her — tell a different story.

This post Maya Parbhoe’s Credibility Crisis: Suriname Unlikely To Be Next Bitcoin Country first appeared on Bitcoin Magazine and is written by Frank Corva. POLITICS, FEATURED, Elections, Legal Tender, Maya Parbhoe, President, Suriname Bitcoin Magazine

Pleb Kruse = BTC foundationalist in exile

Pleb Kruse = BTC foundationalist in exile

(@DrJackKruse)

(@DrJackKruse)